The Catholic church is finally losing its rearguard action

The cover-up of child sexual abuse by the Catholic church is not about sex and it is not about Catholicism. It is not, as Pope Benedict rightly argued in yesterday’s distressingly bland pastoral letter, about priestly celibacy. It is about power.

The urge to prey on children is not confined to the supposedly celibate clergy and exists in all walks of life. We know that it can become systemic in state and voluntary, as well as in religious, institutions. We know that all kinds of organisations – from banks to political movements – can generate a culture of perverted loyalty in which otherwise decent people will collude in crimes «for the greater good».

In none of these respects is the Catholic church unique. What makes it different – and what gives this crisis its depth – is the church’s power. It had the authority, indeed the majesty, to compel victims and their families to collude in their own abuse and to keep hideous crimes secret for decades. It is that system of authority that is at the heart of corruption. And that is why Benedict’s pastoral letter, for all its expressions of «shame and remorse», is unable to deal with the central issue. The only adequate response to the crisis is a fundamental questioning of the closed, hierarchical power system of which the pope himself is the apex and the embodiment. It was never remotely likely that Benedict would be able to understand those questions, let alone answer them.

Smyth emerged as a public figure in 1994 when he was convicted in Belfast after almost half a century of child abuse. He almost destroyed the reputation of Brady’s predecessor, Cahal Daly. He even contributed to the fall of Albert Reynolds’s government in 1994. It makes a kind of grim sense that his horrific career, and the failure of the church to take any real steps to stop him, has re-emerged to haunt another cardinal.

For the shock that Smyth’s exposure delivered to Irish Catholicism has not yet been absorbed by the hierarchy. Both in Ireland and worldwide, the institution’s all-male leadership refuses to face the fact that its own existence is at the heart of the problem. A closed system of authority in which democracy is a dirty word, secrecy is a virtue and unaccountable individuals combine spiritual prestige and temporal power is a breeding ground for abuse and cover-up.

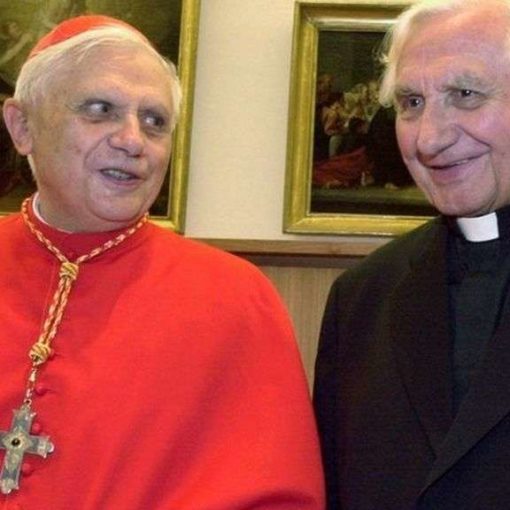

The universal nature of the church’s response to abuse, from Belfast to Brazil and Australia to Austria, tells us the institution itself is the problem. Much of the criticism has focused, understandably, on the actions of individuals such as Brady when he investigated Smyth in 1975 or Benedict (Joseph Ratzinger as he then was) who sent an abuser in his Munich archdiocese for «therapy» in 1980. But the system for dealing with these crimes was the same everywhere: swear the victims to secrecy; send the abuser to be «cleansed» in a clinic; shift him to another parish (or in extreme cases like Smyth’s to another country); and, above all, do not tell the police.

It is not a coincidence that the cover-up worked in the same way throughout the church’s vast domain. It was a fully thought-through system with a clear set of goals, defined by last year’s devastating Murphy report on the Dublin archdiocese as «the maintenance of secrecy, the avoidance of scandal, the protection of the reputation of the church, and the preservation of its assets».

Why did bishops, who were not monsters and who presumably believed themselves to be exemplars of goodness, choose to send child rapists out into parishes rather than bring the institution into disrepute? The brutally truthful answer is: because they could. There is no starker illustration of the corrupting influence of excessive power.

That power was, in Catholic societies or communities, all-encompassing. It included the notion that they themselves and their priests belonged to a special caste, which was not subject to civil law. This idea is deeply ingrained. Only last week, one of Ireland’s leading canon lawyers, Monsignor Maurice Dooley, insisted on RTE radio that priests do not have to report child abuse: «Priests are not auxiliary policemen… they do not have an obligation to go down to the police.» On the contrary, he insisted, Brady, when he learned of Smyth’s crimes, «was dealing with a particular in-camera investigation within the church. It would be a violation of his obligations if he went to the police».

That appalling arrogance was bolstered by an even more sinister knowledge. Bishops and priests knew that, because of their spiritual authority, they could manipulate the victims into feeling guilty. Kindly priests would offer those who disclosed abuse absolution of their sins as if they were the ones who had stains on their souls. And parents who reported the violation of their children were often fearful lest they themselves be seen to be damaging the church they loved. As a previous archbishop of Dublin, Dermot Ryan, noted in internal case notes: «The parents involved have, for the most part, reacted with what can only be described as incredible charity. In several cases, they were quite apologetic about having to discuss the matter and were as much concerned for the priest’s welfare as for their child and other children.»

It is that capacity to place yourself above the law and to make those who have been wronged feel «quite apologetic» that is peculiar to the church. These are the factors that explain, not just why the institution put its own interests above those of children, but also why it succeeded for so long. The church is not alone in believing that evil could be tolerated for a «good cause». But it was unique in the democratic world in its ability to get away with doing so in case after case and for decade after decade.

To cut out the source of the corruption, the church would have to attack its own authoritarian culture. Had Benedict done so in his pastoral letter, it would have been the most dramatic moment in the history of Christianity since Paul fell off his horse on the road to Damascus.

Benedict, as Cardinal Ratzinger, was one of the key figures in the Catholic counter-revolution. His career has been all about rolling back the democratic ideal of the church as the «people of God» that emerged from Vatican II and re-establishing hierarchical control. Indeed, in the pastoral letter, he slyly suggests that Vatican II itself was responsible for the church’s collusion with abusing priests – which, given the existence of precisely the same system long before the council, is patent nonsense.

So, for all the breast-beating in the pastoral letter, there is no acknowledgement of Benedict’s own culpability. (If the «credibility and effectiveness» of Irish bishops have been undermined, as he says, by the scandals, what of his own standing as a bishop, as the power behind John Paul II’s throne and now as pope?)

There is no explicit endorsement of the new protocols in Ireland demanding that all suspicions be referred to the police. Indeed, the demand that «the child safety norms of the church in Ireland» be «applied fully and impartially in conformity with canon law», and the weasel-worded injunction to «co-operate with the civil authorities in their area of competence», seems to reinforce the notion that canon law matters more than criminal law.

There is no rowing back on the line enunciated by the Vatican’s secretary of state, Tarcisio Bertone, last week that «the church still enjoys great confidence on the part of the faithful; it is just that someone is trying to undermine that». That «someone» is, in fact, the church’s own leadership and its unshaken commitment to hierarchical power. The faithful have known that for a long time now. The pope, their supposed leader, is still floundering, far, far behind them.

Fintan O’Toole is an assistant editor of The Irish Times and author of Ship of Fools: How Stupidity and Corruption Sank the Celtic Tiger